SSH Handshake

Overview

SSH, or secure shell, is a secure protocol and the most common way of safely administering remote servers. Using a number of encryption technologies, SSH provides a mechanism for establishing a cryptographically secured connection between two parties, authenticating each side to the other, and passing commands and output back and forth.

In this post we discuss the underlying algorithms and encryption techniques that SSH employs to establish secure connections between two hosts ; a client and server.

Understand Encryption and Cryptography

In order to secure the transmission of information, SSH employs a number of different types of data manipulation techniques at various points in the transaction. These include forms of symmetrical encryption, asymmetrical encryption, and hashing. Understanding these can be useful for understanding the various layers of encryption and the different steps needed to form a connection and authenticate both parties.

Symmetrical Encryption

Symmetrical encryption is a type of encryption where one key can be used to encrypt messages to the opposite party, and also to decrypt the messages received from the other participant. This means that anyone who holds the key can encrypt and decrypt messages to anyone else holding the key.

This type of encryption scheme is often called “shared secret” encryption, or “secret key” encryption. There is typically only a single key that is used for all operations, or a pair of keys where the relationship is easy to discover and it is trivial to derive the opposite key.

Symmetric keys are used by SSH in order to encrypt the entire connection. Contrary to what some users assume, public/private asymmetrical key pairs that can be created are only used for authentication, not the encrypting the connection. The symmetrical encryption allows even password authentication to be protected against snooping.

Asymmetrical Encryption

Asymmetrical encryption is different from symmetrical encryption in that to send data in a single direction(server to client), two associated keys are needed. One of these keys is known as the private key, while the other is called the public key.

The public key can be freely shared with any party. It is associated with its paired key, but the private key cannot be derived from the public key. The mathematical relationship between the public key and the private key allows the public key to encrypt messages that can only be decrypted by the private key. This is a one-way ability, meaning that the public key has no ability to decrypt the messages it writes, nor can it decrypt anything the private key may send it.

The private key should be kept entirely secret and should never be shared with another party. This is a key requirement for the public key paradigm to work. The private key is the only component capable of decrypting messages that were encrypted using the associated public key. By virtue of this fact, any entity capable decrypting these messages has demonstrated that they are in control of the private key.

SSH utilizes asymmetric encryption in a few different places. During the initial key exchange process used to set up the symmetrical encryption (used to encrypt the session), asymmetrical encryption is used. In this stage, both parties produce temporary key pairs and exchange the public key in order to produce the shared secret that will be used for symmetrical encryption.

The more well-discussed use of asymmetrical encryption with SSH comes from SSH key-based authentication. SSH key pairs can be used to authenticate a client to a server. The client creates a key pair and then uploads the public key to any remote server it wishes to access. This is placed in a file called authorized_keys within the ~/.ssh directory in the user account’s home directory on the remote server.

After the symmetrical encryption is established to secure communications between the server and client, the client must authenticate to be allowed access. The server can use the public key in this file to encrypt a challenge message to the client. If the client can prove that it was able to decrypt this message, it has demonstrated that it owns the associated private key. The server then can set up the environment for the client.

Hashing

Another form of data manipulation that SSH takes advantage of is cryptographic hashing. Cryptographic hash functions are methods of creating a succinct “signature” or summary of a set of information. Their main distinguishing attributes are that they are never meant to be reversed, they are virtually impossible to influence predictably, and they are practically unique.

Using the same hashing function and message should produce the same hash; modifying any portion of the data should produce an entirely different hash. A user should not be able to produce the original message from a given hash, but they should be able to tell if a given message produced a given hash.

Given these properties, hashes are mainly used for data integrity purposes and to verify the authenticity of communication. The main use in SSH is with HMAC, or hash-based message authentication codes. These are used to ensure that the received message text is intact and unmodified.

As part of the symmetrical encryption negotiation outlined above, a message authentication code (MAC) algorithm is selected. The algorithm is chosen by working through the client’s list of acceptable MAC choices. The first one out of this list that the server supports will be used.

Each message that is sent after the encryption is negotiated must contain a MAC so that the other party can verify the packet integrity. The MAC is calculated from the symmetrical shared secret, the packet sequence number of the message, and the actual message content.

The MAC itself is sent outside of the symmetrically encrypted area as the final part of the packet. Researchers generally recommend this method of encrypting the data first, and then calculating the MAC

How does SSH Work ?

The SSH protocol employs a client-server model to authenticate two parties and encrypt the data between them.

The server component listens on a designated port for connections. It is responsible for negotiating the secure connection, authenticating the connecting party, and spawning the correct environment if the credentials are accepted.

The client is responsible for beginning the initial TCP handshake with the server, negotiating the secure connection, verifying that the server’s identity matches previously recorded information, and providing credentials to authenticate.

An SSH session is established in two separate stages. The first is to agree upon and establish encryption to protect future communication. The second stage is to authenticate the user and discover whether access to the server should be granted.

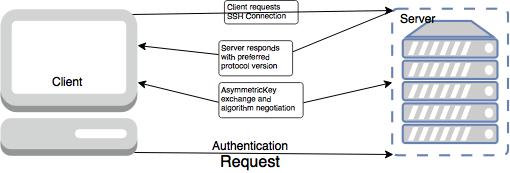

Event Sequence of an SSH Connection

The following series of events help protect the integrity of SSH communication between two hosts.

- A cryptographic handshake is made so that the client can verify that it is communicating with the correct server.

- The transport layer of the connection between the client and remote host is encrypted using a symmetric cipher.

- The client authenticates itself to the server.

- The remote client interacts with the remote host over the encrypted connection.

Transport Layer

The primary role of the transport layer is to facilitate safe and secure communication between the two hosts at the time of authentication and during subsequent communication. The transport layer accomplishes this by handling the encryption and decryption of data, and by providing integrity protection of data packets as they are sent and received. The transport layer also provides compression, speeding the transfer of information.

Once an SSH client contacts a server, key information is exchanged so that the two systems can correctly construct the transport layer. The following steps occur during this exchange:

Keys are exchanged

- The public key encryption algorithm is determined

- The symmetric encryption algorithm is determined

- The message authentication algorithm is determined

- The hash algorithm is determined

During the key exchange, the server identifies itself to the client with a unique host key. If the client has never communicated with this particular server before, the server’s host key will be unknown to the client and it will not connect. OpenSSH gets around this problem by accepting the server’s host key after the user is notified and verifies the acceptance of the new host key. In subsequent connections, the server’s host key is checked against the saved version on the client, providing confidence that the client is indeed communicating with the intended server. If, in the future, the host key no longer matches, the user must remove the client’s saved version before a connection can occur.

SSH is designed to work with almost any kind of public key algorithm or encoding format. After an initial key exchange creates a hash value used for exchanges and a shared secret value, the two systems immediately begin calculating new keys and algorithms to protect authentication and future data sent over the connection.

After a certain amount of data has been transmitted using a given key and algorithm (the exact amount depends on the SSH implementation), another key exchange occurs, generating another set of hash values and a new shared secret value. Even if an attacker is able to determine the hash and shared secret value, this information is only useful for a limited period of time.

Negotiating Encryption for the Session

When a TCP connection is made by a client, the server responds with the protocol versions it supports. If the client can match one of the acceptable protocol versions, the connection continues. The server also provides its public host key, which the client can use to check whether this was the intended host.

At this point, both parties negotiate a session key using a version of something called the Diffie-Hellman algorithm. This algorithm (and its variants) make it possible for each party to combine their own private data with public data from the other system to arrive at an identical secret session key.

The session key will be used to encrypt the entire session. The public and private key pairs used for this part of the procedure are completely separate from the SSH keys used to authenticate a client to the server.

The basis of this procedure for classic Diffie-Hellman is:

- Both parties agree on a large prime number, which will serve as a seed value.

- Both parties agree on an encryption generator (typically AES), which will be used to manipulate the values in a predefined way.

- Independently, each party comes up with another prime number which is kept secret from the other party. This number is used as the private key for this interaction (different than the private SSH key used for authentication).

- The generated private key, the encryption generator, and the shared prime number are used to generate a public key that is derived from the private key, but which can be shared with the other party.

- Both participants then exchange their generated public keys.

- The receiving entity uses their own private key, the other party’s public key, and the original shared prime number to compute a shared secret key. Although this is independently computed by each party, using opposite private and public keys, it will result in the same shared secret key.

- The shared secret is then used to encrypt all communication that follows.

- The shared secret encryption that is used for the rest of the connection is called binary packet protocol. The above process allows each party to equally participate in generating the shared secret, which does not allow one end to control the secret. It also accomplishes the task of generating an identical shared secret without ever having to send that information over insecure channels.

The generated secret is a symmetric key, meaning that the same key used to encrypt a message can be used to decrypt it on the other side. The purpose of this is to wrap all further communication in an encrypted tunnel that cannot be deciphered by outsiders.

After the session encryption is established, the user authentication stage begins.

Authenticating the User’s Access to the Server

The next stage involves authenticating the user and deciding access. There are a few different methods that can be used for authentication, based on what the server accepts.

The simplest is probably password authentication, in which the server simply prompts the client for the password of the account they are attempting to login with. The password is sent through the negotiated encryption, so it is secure from outside parties.

Even though the password will be encrypted, this method is not generally recommended due to the limitations on the complexity of the password. Automated scripts can break passwords of normal lengths very easily compared to other authentication methods.

The most popular and recommended alternative is the use of SSH key pairs. SSH key pairs are asymmetric keys, meaning that the two associated keys serve different functions.

The public key is used to encrypt data that can only be decrypted with the private key. The public key can be freely shared, because, although it can encrypt for the private key, there is no method of deriving the private key from the public key.

Authentication using SSH key pairs begins after the symmetric encryption has been established as described in the last section. The procedure happens like this:

- The client begins by sending an ID for the key pair it would like to authenticate with to the server.

- The server check’s the authorized_keys file of the account that the client is attempting to log into for the key ID.

- If a public key with matching ID is found in the file, the server generates a random number and uses the public key to encrypt the number.

- The server sends the client this encrypted message.

- If the client actually has the associated private key, it will be able to decrypt the message using that key, revealing the original number.

- The client combines the decrypted number with the shared session key that is being used to encrypt the communication, and calculates the MD5 hash of this value.

- The client then sends this MD5 hash back to the server as an answer to the encrypted number message.

- The server uses the same shared session key and the original number that it sent to the client to calculate the MD5 value on its own. It compares its own calculation to the one that the client sent back. If these two values match, it proves that the client was in possession of the private key and the client is authenticated.

- As you can see, the asymmetry of the keys allows the server to encrypt messages to the client using the public key. * The client can then prove that it holds the private key by decrypting the message correctly. The two types of encryption that are used (symmetric shared secret, and asymmetric public-private keys) are each able to leverage their specific strengths in this model.

Channels

After a successful authentication over the SSH transport layer, multiple channels are opened via a technique called multiplexing[1]. Each of these channels handles communication for different terminal sessions and for forwarded X11 sessions.

Both clients and servers can create a new channel. Each channel is then assigned a different number on each end of the connection. When the client attempts to open a new channel, the clients sends the channel number along with the request. This information is stored by the server and is used to direct communication to that channel. This is done so that different types of sessions will not affect one another and so that when a given session ends, its channel can be closed without disrupting the primary SSH connection.

Channels also support flow-control, which allows them to send and receive data in an orderly fashion. In this way, data is not sent over the channel until the client receives a message that the channel is open.

The client and server negotiate the characteristics of each channel automatically, depending on the type of service the client requests and the way the user is connected to the network. This allows great flexibility in handling different types of remote connections without having to change the basic infrastructure of the protocol.

Passwords vs Public Keys

If password authentication is chosen as a standard, then the only credentials used to authenticate a user are sent (encrypted, of course) across the network from client to server. If public key authentication is chosen, neither the private key nor the associated passphrase leave the client. So, on one hand, the only piece an attacker needs is transmitted; and on the other hand neither piece is transmitted. At first glance, it might seem like a simple decision, but there is much more.

Password aging can easily be enforced on the server where SSH runs, while key pairs are less likely to be changed at regular intervals. If an attacker obtained a private key, he would be able to access the server for a much longer period before a switch locked him out. If a central source such as LDAP or PKI was available, key pairs could change more frequently without much work; but this isn’t always possible.

Attackers wishing to circumvent security by sniffing a password would have to stage a mitm or similar type of attack. One option discussed earlier involves DNS redirection to a server capable of logging keystrokes. Even then, an adversary would need to wait until the user attempted to login and hope that the server authentication warning is ignored. Remote brute force is also an option, but extremely noisy and requires a presense online, which in easier to detect. This makes password sniffing and guessing difficult.

Furthermore, a private key can be brute forced off-line if it is encrypted with a passphrase, and no one would know it was being conducted. This is assuming the private key is actually encrypted like it should be, which might be hard to manage and enforce. This type of attack of course would not be possible without somehow gaining access to a user’s private key file. Likewise, if an attacker first gains access to a shadow or SAM database, passwords can be brute forced off-line just as easily.

The immediate solution is to apply complexity requirements for the password or passphrase. Users are always resistant to choosing complex passwords, because they’re difficult to remember, but at least an operating system can enforce a policy (ie via PAM) for passwords, whereas this is not so easy with key pairs.

Password authentication and public key authentication both utilize cryptography, but in different ways. Using public key, a server dictates the supported algorithms for creating the keys. SSH2 requires DSS and recommends RSA. It will not accept use of any less secure algorithms without custom configuration, however DSS and RSA happen to be quite strong. In other words, it’s relatively safe by default. Passwords on the other hand rely on mechanisms offered by the server operating system. Some modern installations still allow password hashing with algorithms based on DES, a completely intolerable system these days. A small number even select DES by default.

While this is certainly not an exhaustive list of pros and cons, it should get some ideas flowing. SSH2 is very flexible and does it’s job well, but as previously warned - a small configuration error or weak cryptosystem could spoil all of it’s goals.

Conclusion

Learning about the connection negotiation steps and the layers of encryption at work in SSH can help you better understand what is happening when you login to a remote server. Hopefully, you now have a better idea of relationship between various components and algorithms, and understand how all of these pieces fit together.

Leave a Comment